CONSTRUIR LA MEMORIA

Memoria y dispositivo

Desde una perspectiva anclada en la tradición, las artes visuales han sustentado con insistencia un predominio de la espacialidad a la hora de configurar sus producciones instituyendo, en ese movimiento, una deposición del tiempo. Los ensayos sobre pintura de Lessing, en el siglo XVIII, dejan constancia de la imposibilidad de dicha disciplina a la hora de plasmar la temporalidad.

En un sentido convergente Sigfried Kracauer, en 1927, y Walter Benjamin, en 1935, coinciden en el sentido desplegado por el dispositivo fotográfico: la sustracción de lo registrado a su historia, a su tradición. Sustracción que opera como un detenimiento del tiempo, en tanto que la fotografía elimina de lo retratado el paso de este. Perspectiva compartida tanto por los teóricos André Bazin como por Roland Barthes.

Quizá la insistencia futurista por plasmar el movimiento, en las primeras décadas del siglo XX, haya tentado un modo de incorporación de la temporalidad en la bidimensionalidad del plano. Así, tanto las pinturas de Carrá y Severini pero especialmente las fotografías de Bragaglia (quien utiliza largos tiempo de exposición), asumen una deuda con los experimentos cronofotográficos que Muybridge y Marey desarrollaran en el siglo XIX.

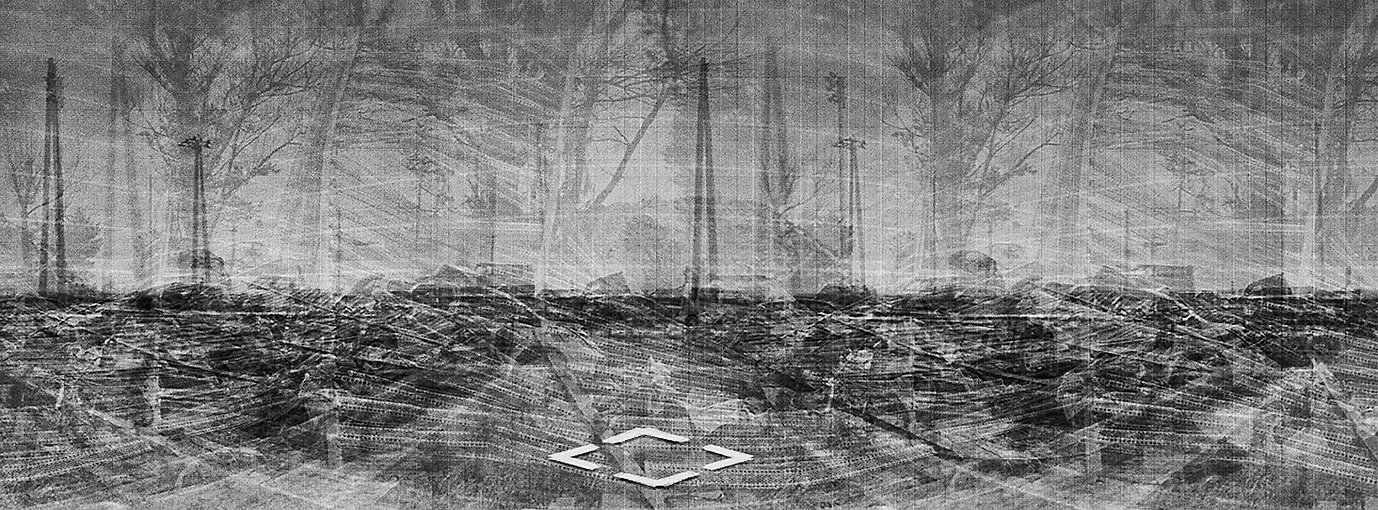

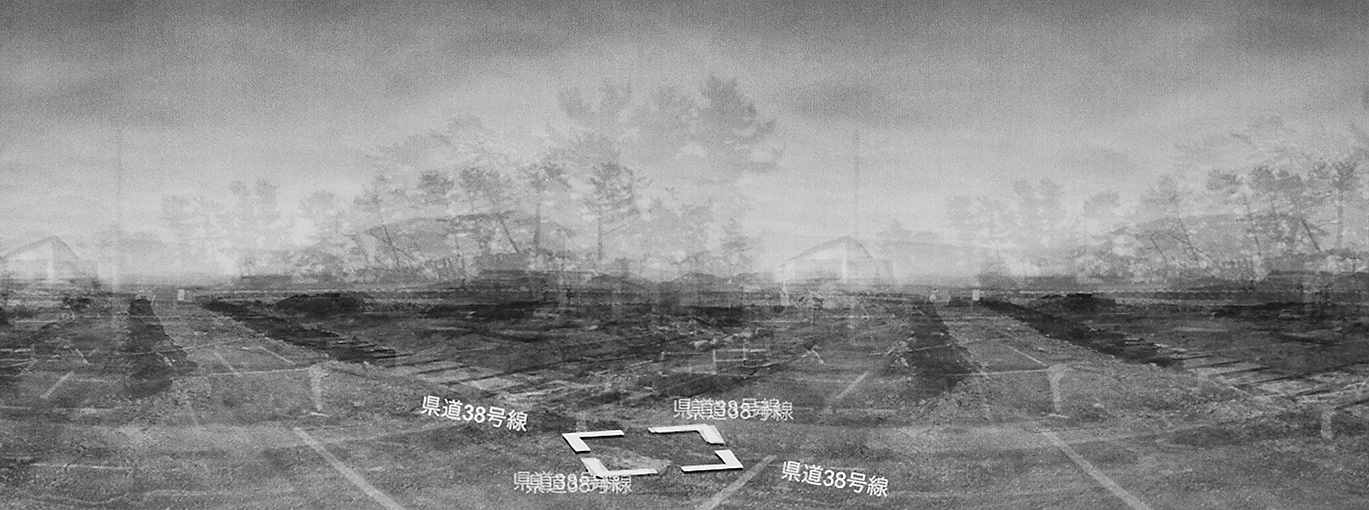

La serie de fotografías Construir la memoria, de Ariel Ballester, se inscribe en esta línea reflexiva en donde la temporalidad se apodera de lo fotográfico, pero, en este caso, hibridándose con una compleja y múltiple red de dispositivos tecnológicos cuyo eje aparece determinado por la web.

Como señala Deleuze, la memoria es un virtual que se actualiza, lo cual implica un entrecruzamiento temporal y, en cierto sentido, una imposibilidad de establecimiento preciso entre las lógicas del presente y del pasado, en la medida en que este irrumpe en nuestra actualidad.

Esta lógica de la memoria se ve, a su vez, intersecada por una tradición que es constitutiva del universo de los dispositivos de registro, en su intento de examinar la otredad: el viaje. Es así como Ballester se ve compelido a realizar un viaje, vía web, a la territorialidad del Japón devastado por la furia de la naturaleza. Y es así como, instalado virtualmente en una de esas calles captura vistas de los cuatro puntos cardinales de ese universo desolado.

Pero como la técnica contemporánea todo lo puede, fue posible que Ballester, emplazado en el mismo punto de vista, pudiera registrar las mismas vistas del mismo sitio pero antes de la catástrofe. Con posterioridad, superpone las ocho imágenes, es decir el antes y el después, el pasado y el ahora, para generar un video, que puesto en loop le permite realizar una toma fotográfica del mismo, la cual es expuesta por el artista durante un minuto y cuarenta segundos, tiempo aproximado de la duración del sismo.

Como huella de la visita virtual, quedan en el extremo inferior de las imágenes, las marcas indelebles del posicionamiento del artista, quizá como una invitación al espectador a experimentar una nueva dimensión de la temporalidad y, por lo tanto, de la memoria, pero esta vez en clave tecnológica.

Jorge Zuzulich.

Memory and device

From a perspective rooted in tradition, visual arts have strongly supported a predominance of spatiality when setting productions; instituting, in that movement, a time deposition. In the eighteenth century, Lessing’s essays on painting are proof of the impossibility of such discipline when translating temporality.

Convergently, Sigfried Kracauer, in 1927 and WalterBenjamin, in 1935 agree on the sense deployed by the photographic device: a subtraction of what was registered through its history, its tradition. This subtraction operates as a time detention whereas photography eliminates from the portrayed the pass of such time. Such perspective is shared by theorists such as André Bazin and Roland Barthes.

Perhaps, the futurist insistence on capturing movement during the first decades of the 20th century has tempted a way of incorporating temporality into the plane’s bidimensionality. Thus, both Carrá and Severini’s paintings, but especially the Bragaglia’s photographs, who uses long-exposure times, assume a debt to chrono photographic experiments that Muybridge and Marey developed in the 19th century.

Ariel Ballester’s series of photographs Construir la memoria, is part of this reflexive line where temporality seizes the photographic but, in this case, hybridizing it with a complex and multiple network of technological devices whose axis appears determined by the web.

As stated by Deleuze, memory is something virtual that is updated, which implies a temporal intertwinement and, in a sense, an inability to establish accuracy between the logics of the present and the past to the extent in which it (such past) breaks into our present.

This logic of memory is, in turn, intersected by a tradition that is constitutive of the universe of recording devices in an attempt to examine the otherness: the journey.

So, Ballester is compelled to take a trip, via the web, to the territoriality of Japan devastated by the fury of nature. Virtually installed in one of those streets, he captures views of the four corners of the desolate universe. As contemporary art can do everything, it was possible that Ballester, located at the same point, could register the same views of the same site but before the disaster.

Subsequently, eight superimposed images, this is the before and the after, the past and the now, to create a video that looped, allows for a shooting thereof which is exposed by the artist for one minute and forty seconds, the approximate time duration of the earthquake.

At the bottom of the images, as a footprint of the virtual tour, indelible marks of the artist’s position are left, perhaps as an invitation to the viewer to experience a new dimension of temporality and, therefore, of memory, but this time in a technology key.

Jorge Zuzulich.